On Wednesday evening a lecture — subject, "The Streets of Newport" — was delivered in the Baptist Temple, by the Rev. A. McAuslane. Mr. Henry Phillips presided. The Rev. Lecturer observed that sometimes after the studies of his books, or a walk through the open fields, he had frequently gone up and down the streets of Newport, and by taking notes of what he saw, had learned many invaluable lessons.

Observations and First Impressions

He had been now walking those streets nearly 19 months, and when he consented to deliver a course of lectures, he thought it would be well to look over his notes and tell them what he had seen and heard. One of the first things that struck him in the streets of Newport was the dirt.

The thought had occurred to him, may not these streets be kept cleaner? Why were there not channels on each side of the streets — gutters, as some people called them — with broad open gratings here and there to carry off the waste water? Then, again, why should there not be good crossings, similar to our pavements, over which people might pass from one side to the other? And why should they not be swept — not in the afternoon — but before six o'clock in the morning?

There was no good reason why this should not be done. There was a vast amount of traffic through the streets, he would grant, but he thought an improvement was very desirable and very practicable, and the sooner it was made the better it would be for all concerned.

Business Taste and Activity

The next thing he noticed in the streets was the taste and activity for business. In looking at many of the shops, he had been impressed with the thought that there was as much taste displayed as in London and other large cities. Taste of this description, however, was not displayed everywhere. In some shops everything was put where it ought not to be.

Such was not according to the right constitution of things, and shopkeepers suffered by it. One day he recommended two ladies to a certain shop as a likely place to get supplied with a suitable bonnet; but, when they went to the shop, they said the window was so untidy that they imagined it was not probable they would find inside what they required. They did not enter, and the individual belonging to that shop lost that evening the price of two new bonnets.

He hoped the time would come when every window would manifest a becoming and modest taste. In conjunction with taste he had noticed also activity. The young men and women were active, and the heads of the establishments also. They knew that if they left business, business would soon be likely to leave them.

Work was healthful, and it was far better to wear out than to rust out. He would say to the young men engaged in business, those who now stand at the head were not all born with silver spoons in their mouths. They had risen, some said by magic — but it was the magic of industry, perseverance, and sagacity, accompanied by sobriety, for no man who tampered with anything that could take away his reason was fitted for business.

Dishonest Advertising

Another thing which he had noticed was the trickery and fraud of business. He did not object to advertising honestly and modestly, but there were some advertisements neither honest, modest, nor truthful.

He had read passing through the streets, "Selling below cost price," "Immense sacrifices," "At any sacrifice," “Goods given away,” &c. The principle involved in these statements was not wrong, but untruthful. There was one shop who advertised that the "Teas sold here are superior to any in the town." Now did they think that the proprietor had examined all the tea at the other shops? No, it was probable that he had seen none but those in his own shop.

The man who sold below cost price would, he thought, soon sell some one else; and to test the truth of the announcement, “Goods given away," let them step into the shop one day, take up the first bale of goods, and walk off with it. These advertisements were not based on integrity, and he would advise the audience to pay no attention whatever to them.

Street Quackery

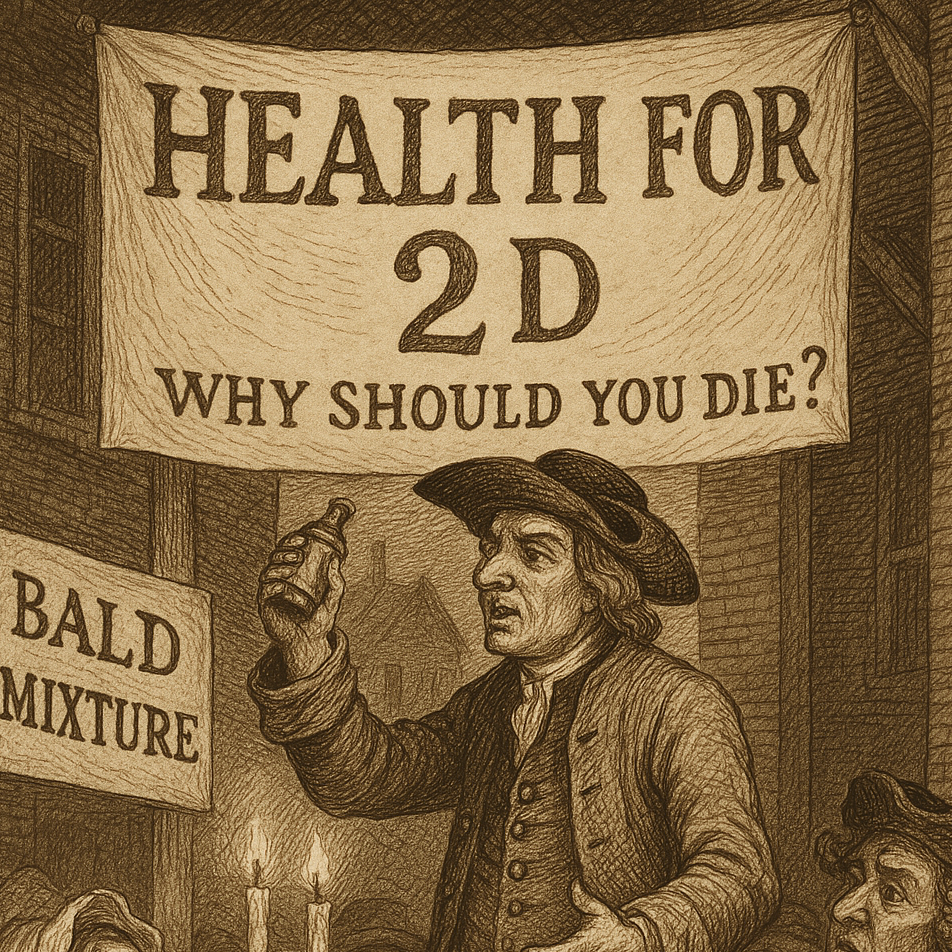

He had also been impressed with the quackery in the streets — in the medicine line. Not long since, he had noticed a man with two candles offering his medicines, that would cure any one, for 2d. His motto was, “Health for 2d. Why should you die?"

For the purpose of giving them an idea of how such persons proceeded, he read an extract from a work containing the address of one of these quacks taken down verbatim, which excited much laughter. They ought to pay no attention to such persons.

Immoral Street Literature

Another thing was the literature of the streets. There were a man and woman who stood by the railway gates when the train was not coming, with a lot of ballads stuck up, and at another time, people would be going through the streets singing them.

There was in these ballads no poetry or sense but a vast amount of impurity, and those who sung them were generally too lazy to work. Not only was this literature dirty literally, but in the modern acceptation of the term.

They had good literature, however, in the town, and the noble Athenaeum contained volumes for all, and there ought to be more readers than there were. He hoped that the taste for good reading would be extended, and that along with the quack doctor, they would send off the lazy fellow who sold and sung this immoral literature.

Beggars and Charity

He had observed, too, stuck on the walls small bills, sometimes of one colour, and sometimes of another; but they were always about health. These bills contained the most scandalous stuff he had ever read; and they ought to come under the act passed some time ago in reference to obscene publications.

He had further noticed the beggars of Newport. They would all agree with him that they paid pretty well for the poors' rate without being afflicted as they were, with a variety of beggars — lame, cripples, &c.

It was a duty to support the poor, but let them be discriminating, as they might give a shilling to a man which would prove a curse to him. There were many deserving poor who never applied to the Union; let them find such out, relieve them, and be kind to them, but let those who came of a suspicious description, go away as they came.

Beer Shops and Public Houses

Again, he could not but notice the beer shops and spirit shops of the town. In some parishes in Scotland they had had Maine laws for a long time. There were no beer shops in them, and no gaol or union.

In Newport were 206 beer shops and 85 general licensed houses, making a total of 291 shops licensed for the sale of intoxicating liquors. They contrived somehow or other to get at the corners of the streets, and about 78 or 80 were thus situated.

There might be many reasons for this, one being that there were then two ways to the house, and was most likely to attract the passers by. What good did these houses do?

Our drapers, grocers, and butchers did a vast amount of good, it could not be denied. Did they ever hear of publicans banding together and getting up lectures for the people?

If these houses were doing good, their aim should be to increase them, and they would never find a single individual on the temperance platform if they were convinced that such was the case. But he was sure they were doing a vast amount of harm, and the sooner they were got rid of the better.

It could not be denied, indeed, that they were the means of increasing crime and the poor rates, and of doing a vast amount of mischief in the town. They should then try to get rid of them as soon as possible.

The Social Evil

These remarks brought him to the last thing which he should mention — one which had grieved him as he witnessed it, and which he could not speak about as he would like. He referred to the “social evil."

In passing up and down the streets of Newport, it was evident the evil was among us. The number of unfortunates, as they were called, were stated in the last report of the chief superintendent to be 287, and it had struck him forcibly that most of them were young.

What had brought these creatures to their present condition? Once they were as free from the evil as it was possible to be. Perhaps some of them had uncomfortable homes or had been led away by some one deemed respectable; or further still, some may have set their affections upon others, who by and by had rejected and left them, and allowed them to sink into degradation.

In whatever way they came into that condition, they ought to command our commiseration instead of being spurned at. They all had souls and were passing into eternity as well as ourselves. Let no man say such things ought to be. It was a shame and disgrace to the civilisation — not to speak of the Christianity — of this country.

He could tell them of what he had witnessed when a town missionary, but that was not the place for him to do so. He had then seen and heard things which enabled him to look upon human nature in a way he had never seen it before, and he was confirmed in the opinion that some men were worse than the devil.

Of those who actively incited this prostitution, all were not young or unmarried men, but some of them were old, and their looks were silvered by age. It was not for him to name them, but God knew them. They should not forget that while they were ruining their bodies they were also ruining their souls.

If there was any one on whom he could spit out his venom, it was on the man who held up his head as respectable, while he, in a steady manner, did all in his power to keep up the evil which existed in our midst.

If we had less beer shops, we should have less poor females. Although there were 55 houses in the town in which they specially lived, most of them lived at the beer shops. They must be fired with drink before they could ply their baneful trade. Get rid then, he would say, of the beer shops.

Closing Remarks

In closing, he would say, notwithstanding the many evils, we lived in good times. There never before were such times in the world’s history; never was there so much good done, or so much prayer offered up, and God seemed to smile upon the efforts that were being made.

There was not an institution for benevolent purposes which they could not name, and their own temperance movement was never in a better position than now. He believed the good time was coming; the more they did to usher it in, the more speedily it would come. The Rev. Lecturer was frequently applauded.

Who was the Rev. Alexander McAuslane?

Alexander McAuslane was born in Dunfermline on 27th April, 1826 and married on 31st October, 1853.

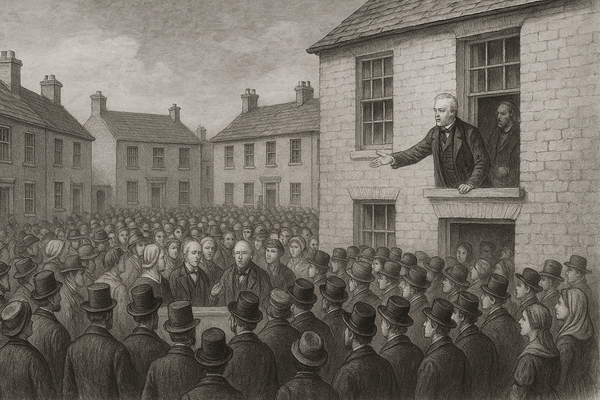

He was living in Lanarkshire in 1853 and then in October 1858 he was formally recognised as pastor of Dock Street Chapel, Newport, after six successful years of ministry in Dunfermline. The ceremony featured prayers, hymns, and addresses from numerous ministers who praised his character and dedication. McAuslane accepted the church’s unanimous invitation, stressing his sense of divine guidance and his mission to uplift all classes of society. The day concluded with a celebratory dinner and well-attended evening meeting, marking a hopeful new chapter for the chapel. (Long article about that day)

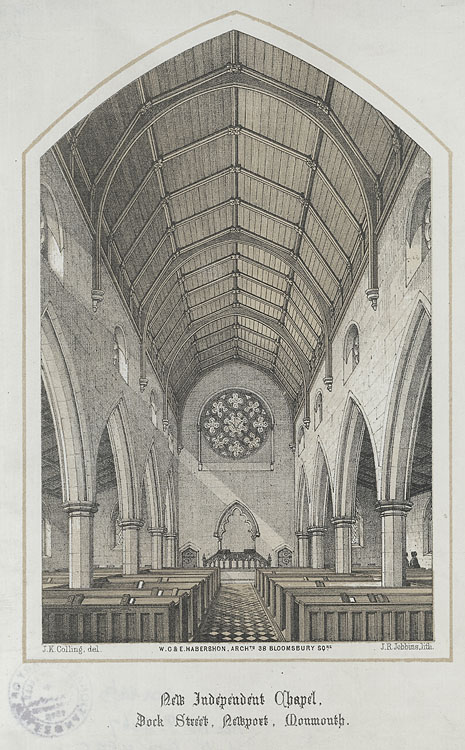

Interior of the Dock Street Chapel in 1865 (Source: Wikimedia) | Map showing the location of the chapel in 1883

He gave lectures such as the one in this article and another in Caerleon in 1861 and by 1871 he had moved on to be a minister in Hackney, London.

Member discussion